Era Endings and New Beginnings

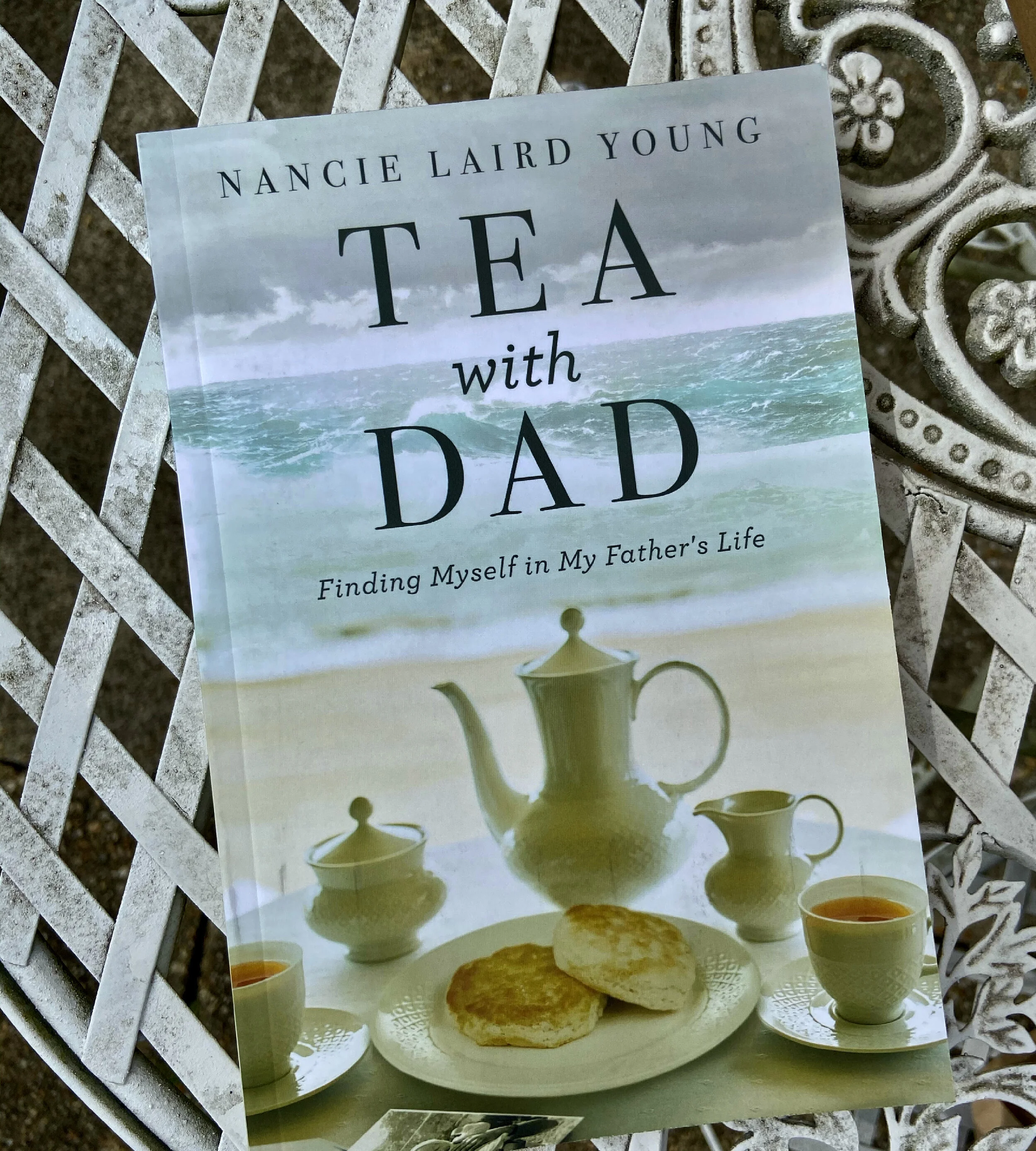

Last June my debut memoir Tea with Dad made it into the world. That marked the passage of three very busy years, during which I interviewed my father, researched dates and addresses, and wrote at night while reading and researching anything I could get my hands on about being an author and marketing a book. I made lots of promises to myself that I didn’t keep. I also slipped, without realizing it, into the life of a full-time caregiver for my Dad. If you read my book, you know that was always the plan, though the new job didn’t start until after the book was published. As usual, distracted, I didn’t notice.

Dad died July 6, 2022. We didn’t think he was going to die when we called the ambulance to take him to the hospital. We thought he was going so that he wouldn’t die, but five hours after arriving and just a few minutes before heading up to the room they prepared for him, he went into cardiac arrest. The corps de ballet of nurses attending him moved as one in what seemed like a slow-motion waltz. I watched from outside the room as they brought him back, his already weak heart too damaged to keep going without support.

The doctors called us and without giving us much information said, “You can come over now, if you’d like.” Since it was outside normal visiting hours for the ICU we knew the news would be bad. I just prayed we were not too late. We weren’t.

“How’s it going, Dad?” my brother asked as we walked in. My father raised his right hand, thumb up and then purposefully thrust it downward. I thought this meant that he wasn’t happy about being in the hospital or being intubated or… and then the doctors came in.

They told us they had not been getting the results they’d hoped for, that the left side of Dad’s heart was not working. Then without really telling us what it meant other than “We’ll see what happens” they told us that Dad wanted the tubes taken out. They assured us they’d spoken to him and that he’d been awake and aware and able to convey his wishes. I watched my father as they told us this. Then I walked over and said, “Dad, they say you want the tubes removed. Is that true?” He nodded. “You are aware of what can happen?”

I thought about how difficult that discussion would have been nine years ago before I moved into his house. Before all our conversations over afternoon tea and during our drives, and dinners together. I thought about how different a person I am now after living with him more during that time than I had as a child.

He looked into my eyes and nodded. Assertive, strong, committed. I knew that look.

“Okay,” I said. The doctors removed everything and within an hour my father slipped away. His body just stopped working. During that time he couldn’t talk to us, due to weakness or the fact that he’d been intubated for so long. But he looked at us with those blue eyes once so clear and bright, now tired.

While we were growing up we always knew that my father might not come home. He was in the Army. At various times he was in areas where combat could occur and, of course, he’d been in Vietnam. He always came home. This time he did not. Three days after his death, my youngest brother looked at me and said, “I think I just realized that Dad is not coming back.”

It broke my heart.

I’m grateful he didn’t linger. That he was conscious until the end. That he was not, at least in the last hours, uncomfortable or in pain. I’m glad we were there. All that gratitude gets in the way of grieving. I can’t seem to find the balance.

The other day my friend Betty reminded me of a passage in the book. It occurred after the first time he was hospitalized a few years ago, when it became clear that his health was deteriorating. The doctor indicated that they could stabilize him and that maybe there would be a need for portable oxygen.

“If I need to have oxygen, it’s over,” he said.

I looked at him.

“I mean it. I can’t play golf with a tank of oxygen.”

I thought he was trying to joke, but when I looked at him, he was serious. He seemed to be telling me that if living required oxygen, his life was over.

I said something he used to say to me when I was a child, worried or afraid, and anticipating the worst: “Let’s wait and see what happens, Dad.” Then I added, “You can’t go anywhere right now. I don’t have a plan B.” I laughed and he grinned at me. It was true. I couldn’t bear for him to die. That was not part of my plan.

“He’s guiding you through Plan B,” my friend Betty wrote to me.

So, I gave myself until today, August 1, 2022, to wallow in the loss of him. From now on I’ll grieve while moving through Plan B, which is not solidified. What in life is?